Leigh Sugar’s Freeland: A Journey of Love and Struggle Through Poetry and Prison Walls

Review by Cid Galicia

“Freeland“

Alice James Books

ISBN: 9781949944730

June 2025

You like me because I’m a scoundrel. There aren’t enough scoundrels in your life.

-Han Solo (The Empire Strikes Back)

There was something so pleasant about that place

Even your emotions have an echo in so much space.

-Gnarels Barkley (Crazy)

Navigating Leigh Sugar’s collection, FREELAND, is like being caught in an argument between Han Solo and Gnarles Barkley on how to rescue the Rebel Princess from the Galactic Empire’s prison, The Death Star. At least they weren’t caught in the 1900s, still naming prisons via historical indigenous geographic locations. Because we are, and Leigh is, and that is where we find ourselves, with her, in this collection.

Freeland, Michigan, is home to the Saginaw Correctional Facility,

a Michigan state prison.

[Established in 1993, the facility’s naming aligns with common practices of identifying institutions by their geographic locations, thereby reflecting the area’s indigenous heritage and historical significance]

Now let’s jump galactic timelines, governments, and rebellions, and lovers back to 2025 when, instead of a senator and a scoundrel, we find a writer and a prisoner. Welcome to Freeland.

In this impactful collection, Leigh writes about the U.S. mass incarceration system, whiteness, both within race and architectural design, and the struggle of sustaining identity and love within the prison industrial complex. It’s an impressive undertaking, but she doesn’t go it alone. She has surrounded herself with a rebel squadron: Edmond Jabes, Phillip Johnson, Solmaz Sharif, Gnarels Barkley, and Natasha Trethewey – just to name a few. You are not alone! You have powerful rogue allies to guide you through the trenches of exile, art, mysticism, and memory – For The Republic!

Collection Opening

What evokes a deep respect for Leigh and her work is her relentless commitment to the truth of her physical and psychological experience in the prison system. She does not give readers a free pass straight to the heart of her detainment center – her collection. That was never offered to her when she would visit her partner. For her to gain access, the process was lonely, vast, and invasive. There are Visiting Standards and protocols:

An officer searches your body like an envelope

Before we meet again in the room of infinite goodbyes

1. Prior Authorization

-Submit a formal request.

-Provide your credentials, purpose, & connection to the inmate

-If approved, you’ll receive written confirmation with the date, time, and duration of the visit.

2. Pre-Visit Preparation

-Review the prison’s visitor rules (e.g., dress code, contraband policy).

-Bring valid government-issued ID and, if required, your press or legal credentials.

-Arrive early to allow time for processing.

3. Entry Process

-Check in at the front desk/lobby.

-Present your ID and approval documents.

-Store personal belongings in a designated locker (phones, wallets, and bags are usually not allowed.)

-Pass through metal detectors and a pat-down or wand search.

-Your materials (notebook, recording device, etc.) must be pre-approved.

-Sign a logbook and possibly receive a visitor badge.

4. Escort to Visitation Room

-A corrections officer will escort you through several secured gates or corridors.

-Inmates may be brought separately and may be in restraints until seated.

5. The Visit

-Usually held in a non-contact room (behind glass) or a supervised contact room.

-Monitored by staff or recorded in some cases.

-Interviews have a time limit (commonly 30–60 minutes).

6. Exit Procedure

-Return badge (if issued).

-Collect belongings.

-Sign out.

-Exit through security.

All right, Cid, this is supposed to be a Poetry book review. How is your editor going to feel about listing the prison’s visitor entry process when you haven’t even touched on theme, style, or anything poetic? Didn’t you get in trouble for this the last time you submitted a review on Sugar’s work?

Yes I did! But here is why, and it’s [enter curse words here] Genius! Leigh is a poetry collection Architectural Jedi! Displayed above are the basic steps to visit a prisoner. At the heart of Freeland is the answer to freedom, yours and hers. But Leigh knows the best way to learn and value what is learnt is to experience it as she did. The physical and psychological requirements needed to gain entry to the heart of a prison, to release the prisoner held within. That experience and that journey are the key to freedom, and she is offering you that key. But you just have to go through the 17-step process to get there!

That’s right before you even get to the first poem in her collection, you have to pass through a 17-page entry process. She is the warden in Freeland, and you will follow her rules.

Here is the initial architecture of her poetry collection:

1. Prior Authorization

-Book Cover (image & title) 1

-Title Page (text only) 2

-Blank Page 3

-Second Title Page (title & image) 4

2. Pre-Visit Preparation

-Publishing Information Page 5

-Table of Contents Page (3 Pages) 6-8

-Blank Page 9

-Informational Quote (from the author) 10

3. Entry Process

-Blank Page 11

-Opening Quote to the Collection (Edmond Jabes) 12

-Blank Page 13

4. Escort to Visitation Room

-Opening Poem to the Collection (Architecture School) 14

-Blank Page 15

-Part 1 Title Page/Quote (Solmaz Sharif) 16

5. The Visit

-Blank Page 17

-First Poem (Inheritance) Page 18!!!!!

Prior Authorization & Pre-Visit Preparation

As part of the pre-visit preparation, Leigh gives us two quotes and the poem Architecture School.

The blank page is not a grid we must adapt to. It will surely become so, but at what price?

-Edmond Jabes

There is nothing that has nothing to do with this.

-Solamz Sharif

Jabes was a Jewish man who was exiled from Egypt due to the Suez Crisis set by the Egyptian President in 1956. Solmaz Sharif is an Iranian poet who used United States Department of Defense Terminology to interrogate the language of war. Why these quotes? Why do they matter? What do they mean?

Alright Rebel Scum, let’s get poetical! Jabes and Sharif both reflect three of Leigh’s thematic threads within the walls of FREELAND: Exile, The Questioning of Form in Art and Society, and Mysticism / Connection. Which leads to her introductory poem: Architecture School.

In this poem, she reflects on the idea of white space, a space that must be added to, subtracted from, or altered in some capacity to create an entity, a structure, or art.

We studied Philip Johnson’s Glass House,

the perennial favorite. Seamless integration into the landscape.

She reflects on her desire for the things we create to add to or modify the landscape, as opposed to desecrating or defiling it. Prisons are designed to secure, surveil, and deter. They are designed to separate both the eyes of its inside world, as well as the eyes of the outside world, from the truths of each other, and the agendas behind that intentionality. With each close read of this collection, your eyes will strengthen as you will see a bit deeper into the prisons you have built for yourself, or have been forced into. The poem closes with this:

What wonder—to see the thing, and through it.

This is her call to use this collection, upon its completion, not as a stopping point, but as a launching – to see deeper into how and where we have found ourselves, and our partner, imprisoned.

Entry Process

Part one of the collection is separated into three sections. The first is a set of poems that ping-pong back and forth between the wars and prisons of her Inheritance, her past, as well as the prison of her present, which holds her and her partner hostage. The last poem of the first section, titled Security, walks you through the conveyor of mechanisms, machines, doors, searches, and body offerings she had to endure to see him. Security is what led me to the architecture of my opening for this review.

OPEN GATE ONE step in

put your keys and your ID on the table walk through

the machine whoops

take your belt off try again

it smells in there by the way OK GATE TWO

Section 2 is intimate and private, an internal dialogue: sometimes to herself, and sometimes to another. She knows all too well that the prisoners, her partner, are not allowed the privilege of intimacy and privacy. So she sacrifices hers to us, the readers, to understand a bit deeper what the outlying and unspoken realms of the prison system feel like to enter.

I pretend I am an anthro-

pologist when I lift my

hair and tongue to show

I hide no drugs or weapons

behind my ears or in my

mouth.

Section 3 is probably my favorite. How in all this, they, Leigh and her prisoner, fight to try and keep each other and their relationship above water, to try and keep the passion of their love alive. At times, it can be the darkness of desperation that invokes in us our ability for ultimate creative measures. Measures of a rebel and a scoundrel. Measure for Fantasy and phone sex! There are a lot of great pieces in this section, but at its center, you will find the Correction’s Vault. A jeweled crown of sonnets.

This braided selection is her heart’s war being pushed to its precipice. Can love survive a prison sentence? Should it be expected to? What is this world that one has to look to the pioneers of poetry to answer these questions? Whose world? Her world, their world, our world. In the end, it is only she– and only she must decide. This shattering 16 sonnets, this call // this struggle // this fighting to escape a reckoning is compulsively concussive to read.

Once you unlock the first, you are its prisoner until the end. And once there, we’ll see how free you feel, probably as free as they do. Probably as free as she does. Each following sonnet is pinned to a line or passionate phrase from the previous, until they entropically implode upon themselves.

In the visiting room I try to reconcile the you

I love with the jumpsuited you beside me.

I confess I want to leave and leave you there.

So far this review only covers the opening and part one of the collection! There are two more major parts, and the corridors, cells, escape routes, and medical centers you coaster through will leave you wet and sweating and in need of…

a white V-neck T-shirt—619754

printed along its body-side bottom hem—

wrapped in a clear plastic garbage bag

an officer hands me to put in the coin-operated locker

before moving through security to see you

You will be sweating and aching because [A Number Is Just A Name].

This is where I will make my final stand, with two personal intersections with this work. Both from deep in my heart as a New Orleans poet and high school educator of 20 years:

The first is because of the School-to-Prison Pipeline. The school-to-prison pipeline in New Orleans refers to the pattern of pushing students, especially those from marginalized communities, out of the public school system and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems. This phenomenon is characterized by harsh disciplinary practices, lack of resources, and inadequate support systems that disproportionately affect students of color and students with disabilities.

The second is because in the third semester of my MFA, my mentor, Kate Gale, assigned me One Big Self by C. D. Wright. (Ms. Sugar was a finalist for the C.D. Wright Poetry Prize in 2024.) C.D. Wright wrote One Big Self, a documentary-poetry project to humanize the incarcerated men and women living through the prison system in Louisiana. In it, she reminds us that they are more than their prisoner identities.

We are all more than our prisons. If you read Freeland, you will hurt a little, heal a little, and hope a lot.

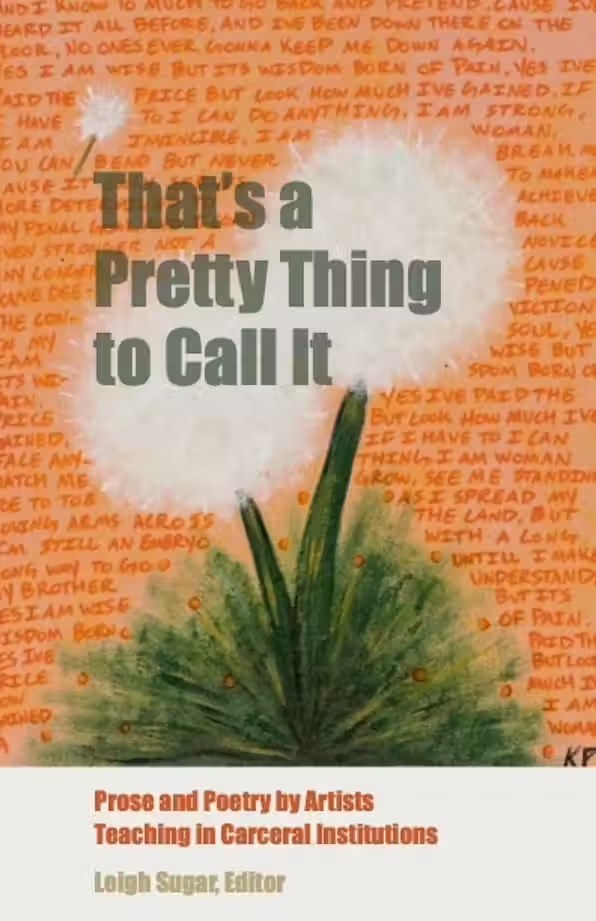

Leigh (she/her) is a writer, teacher, and, most importantly, learner. According to her cardiologist, she is “an extremely pleasant but most unfortunate 34-y/o.” She created and edited That’s a Pretty Thing to Call It: Prose and Poetry by Artists Teaching in Carceral Settings (New Village Press, 2023). Her work appears in POETRY, jubilat, Split this Rock, and more. She teaches poetry workshops through various organizations, including Poetry Foundation, Hugo House, and prisons in Michigan. She also works for Rachel Zucker’s poetry podcast, “Commonplace.”

You can follow her on Instagram @lekasugar

Freeland is available from Alice James Books.